To explain I’ll use an example from wikipedia. Imagine you’re a landscaper for the president. While mowing the white house lawn, you may or may not have accidentally mowed over a garden full of roses planted by Abraham Lincoln himself. Of course, the government decides that justice must be served for this crime, so they arrest you, charge you with desecrating Abraham Lincoln’s memory, and put you in front of a jury.

The case goes on, and your lawyer pulls every legal trick in the book to get you out. Unfortunately, they are outmaneuvered, and eventually it’s time for the jury to make their verdict. They go into deliberations, and as the hours pass you have no choice but to sit and wait in increasing panic. If the jury finds you guilty, you know there can be only one punishment for desecrating Abraham Lincoln’s memory: death.

Suddenly, the president walks in, along with the entire supreme court. They declare that, given the severity of the crime, they are going to suspend the constitution, just this once: instead of a guilty verdict requiring unanimous agreement from the jury, only a simple majority will be required. That is to say, a guilty verdict requires only that at least 7 of the 12 jurors think you’re guilty.

Your eyes go wide. Only 7 out of 12? You’re toast for sure. But immediately after this announcement, court observers begin shouting obscenities and throwing rotten tomatoes at the president. “7 out of 12 required! They’ve gone soft!”

Not wanting to seem soft on crime, the president and supreme court reconvene and make a new announcement. “The mob has spoken!” they declare. “Only 3 out of the 12 jurors voting guilty will be required for a guilty verdict!”

This does not make you feel any better, to put it mildly. You look for reassurance in your lawyer. “What do you think, esquire? Do my odds look good? Will 3 or more of them find me guilty?”

Unfortunately, she doesn’t seem willing to meet your eyes. “I have bad news for you,” she says. “Our jury intelligence network has discovered several facts. First of all, each of the jurors are completely logical individuals. Second of all, they all agree that if you mowed over a garden full of roses planted by Abraham Lincoln himself, and that if doing so qualifies as desecrating Abraham Lincoln’s memory, then you should be found guilty.”

You can’t blame them. “If I mowed his roses, and if mowing over his roses is a crime, then even I must agree that I would have committed a crime. But that doesn’t tell me whether they think I actually mowed his roses, or whether doing so is actually a crime.”

Your lawyer’s lips tighten, and a tear rolls down her cheek. “That’s where it gets worse. We have established conclusively that a majority of the jury believes you have mowed his roses. Furthermore, a majority of the jury believes that mowing his roses is a crime. Therefore, I can only conclude that they will find you guilty.?

Suddenly, the jurors burst from their deliberations. “We the jury, find the defendant……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..”

Challenge Time!

During the dramatic pause, your lawyer turns to you one last time. “You do have one chance,” she says. “The theory of quantum immortality says that as long as your survival is logically possible, it is guaranteed that you will survive in at least one timeline. Since you don’t care about any timelines where you don’t exist, and you don’t exist when you’re dead, that means that from your perspective, you will always survive in any situation where your survival is possible.”

This may not seem like the most reassuring thing your lawyer could possibly say. But it starts you thinking. Is it logically possible that you survive, given that the following is true about the jurors?

They are completely logical

They all think that if you did it and if it’s a crime, then you should be found guilty

A majority think you did it

And a majority think it’s a crime

And of course, just 3 or more out of 12 jurors thinking you’re guilty leads to your inevitable death.

There’s no way, you think. I’m dead for sure. It’s logically necessary.

Finally, their dramatic pause is over…

“We the jury, find the defendant….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….

NOT GUILTY!!!!!”

Confetti rains from the ceiling as the portion of family that has not disowned you jumps for joy. As you walk out of the courthouse, looking up at a sun you were afraid you’d never see again, you wonder where your thought process went wrong.

Suddenly, it hits you.

This was the jury:

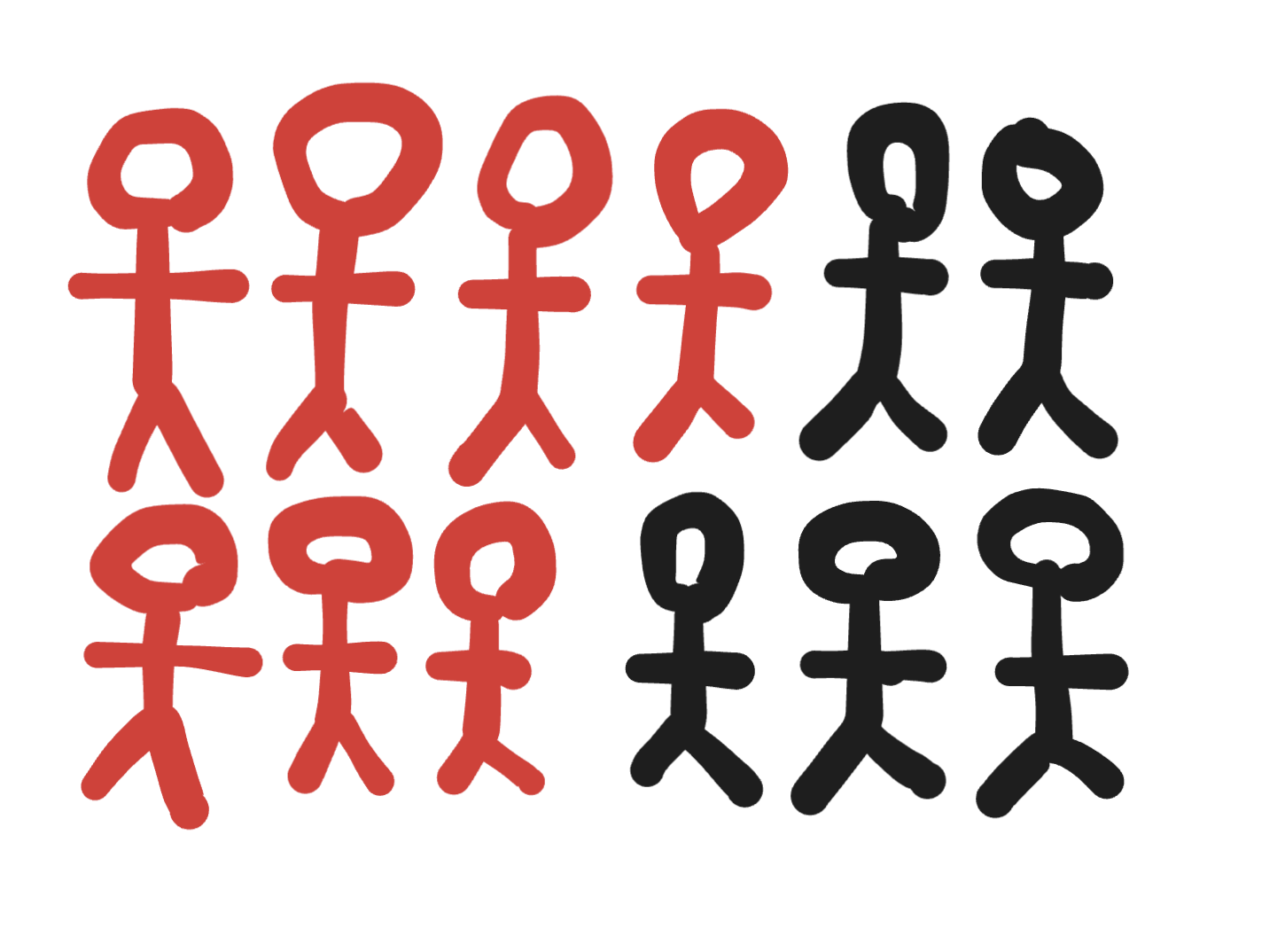

Now, colored in red are the ones that think “you mowed over the flowers”:

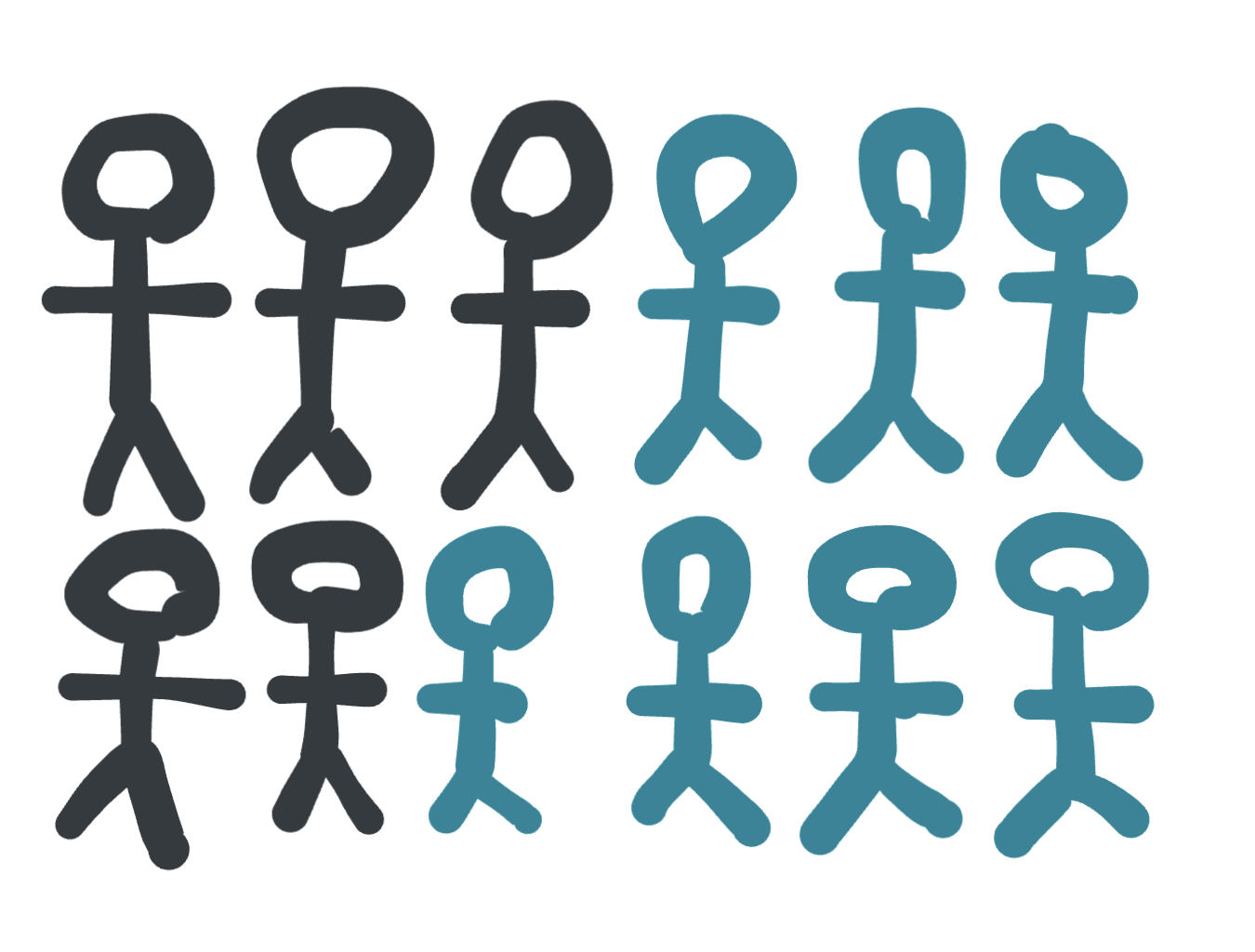

And colored in cyan are those that think “mowing over the flowers would be a crime”:

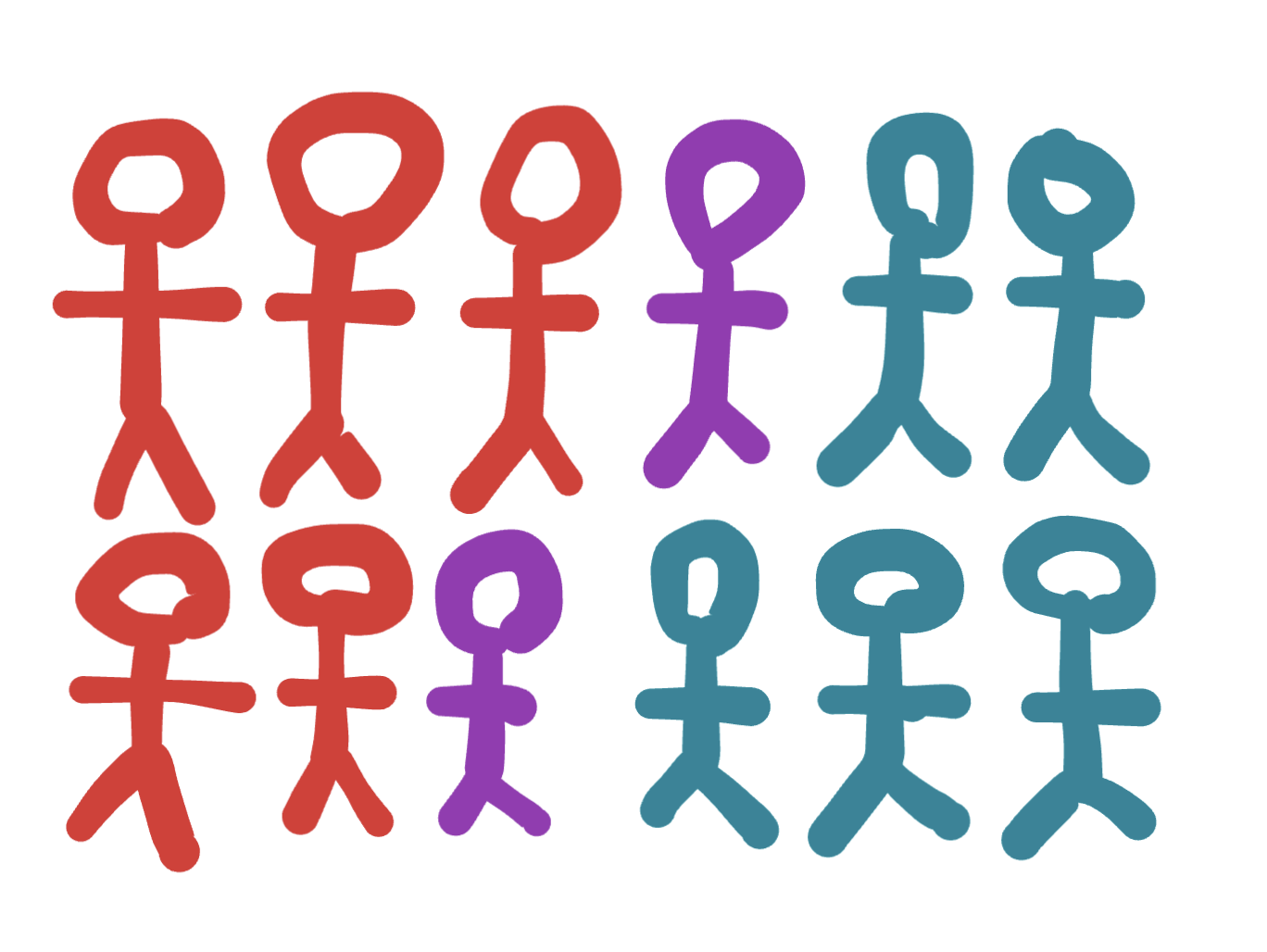

The only ones who would vote guilty are those in both the red AND cyan sections, who I’ll make purple:

That’s only two jurors! So you did not reach 3 guilty votes, and live to landscape another day.

Huzzah!

Hi. I have a couple of criticisms of your writing style.

1. I would prefer to see the content of the title repeated, summarized, or reintroduced at the beginning of the body of text. There was a jarring discontinuity between "My new favorite paradox: The Doctrinal Paradox" and "To explain I’ll use an example from wikipedia", when the second sentence heavily relies on the first phrase in order to make sense.

2. You wrote 1000 words just to pose an arithmetic oddity. The core problem was this: "Is it possible that: 1) the majority of 12 people agree with X, 2) the majority of 12 people agree with Y, and 3) less than 3 of those 12 people agree with both X and Y?". Halfway down this article, I realized that this was the problem being proposed. I paused reading to try to do the math in my head, and figured out that the answer was "yes". Then I continued reading, until I got to the final word: "Huzzah!". In this context, "Huzzah!" means "Yep! That's it! There's nothing more to say!".

3. Could you have explained the significance of this paradox? Could you explain why it seems counterintuitive? Are there any real-world examples of this paradox that have led to shocking consequences?

4. When you posted this link to the Slate Star Codex subreddit, you mentioned that "[This paradox] extends the voting paradox and Arrow's theorem to situations where the goal is to combine different sources of information or judgments, rather than preferences". I recall seeing the explanation and derivation of Arrow's Impossibility Theorem, and my mind was blown. It took me a lot more than 60 seconds to grasp the complexity of it and its implications. Again, I repeat, this doctrinal paradox— as you have explained it— seems so trivial that it doesn't really deserve to be mentioned alongside those seminal theses of social science.

Keep writing more. Keep getting better at writing. I'm just giving you feedback about the mindset of a reader like me.

I love your writing style. Also, Daniel Munoz commented about this paradox under my post on the goomba fallacy, which apparently has the same root. Who woulda thunk?